The Washington Post article on motorcycles Adrenaline Crew

Wheelie Dealing

After Years of Stunts, the Adrenalin Crew Is Getting Its Big Break — and This One Isn’t Painful

By Lonnae O’Neal Parker

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, September 20, 2005; C01

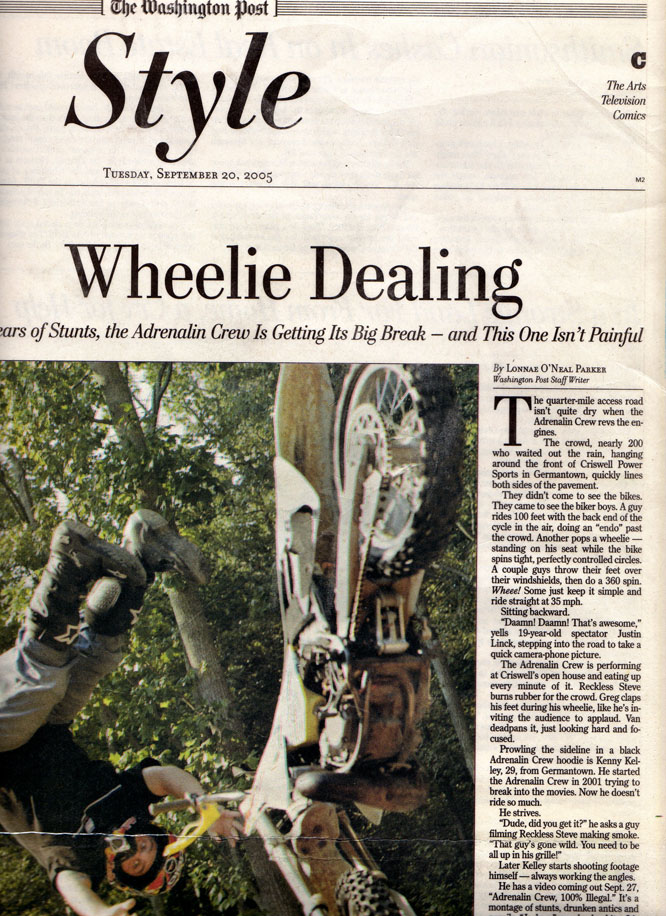

The quarter-mile access road isn’t quite dry when the Adrenalin Crew revs the engines.

The quarter-mile access road isn’t quite dry when the Adrenalin Crew revs the engines.

The crowd, nearly 200 who waited out the rain, hanging around the front of Criswell Power Sports in Germantown, quickly lines both sides of the pavement.

They didn’t come to see the bikes. They came to see the biker boys. A guy rides 100 feet with the back end of the cycle in the air, doing an “endo” past the crowd. Another pops a wheelie — standing on his seat while the bike spins tight, perfectly controlled circles. A couple guys throw their feet over their windshields, then do a 360 spin. Wheee! Some just keep it simple and ride straight at 35 mph.

Sitting backward.

“Daamn! Daamn! That’s awesome,” yells 19-year-old spectator Justin Linck, stepping into the road to take a quick camera-phone picture.

The Adrenalin Crew is performing at Criswell’s open house and eating up every minute of it. Reckless Steve burns rubber for the crowd. Greg claps his feet during his wheelie, like he’s inviting the audience to applaud. Van deadpans it, just looking hard and focused.

Prowling the sideline in a black Adrenalin Crew hoodie is Kenny Kelley, 29, from Germantown. He started the Adrenalin Crew in 2001 trying to break into the movies. Now he doesn’t ride so much.

He strives.

“Dude, did you get it?” he asks a guy filming Reckless Steve making smoke. “That guy’s gone wild. You need to be all up in his grille!”

Later Kelley starts shooting footage himself — always working the angles.

He has a video coming out Sept. 27, “Adrenalin Crew, 100% Illegal.” It’s a montage of stunts, drunken antics and puerile “Jackass”-on-wheels skits. It’s his first production with a big U.S. distribution deal. It’s the first one that’ll be for sale at Best Buy and Tower Records, and getting here has been tough.

Since the beginning, the Crew has been eight or so core guys around the country, with others showing up when they can. They split because they’ve got to make money and Kelley can’t always pay, because they’ve lost their driver’s license or their bike. They drop in and out while Kelley perseveres, steering, trying to hold his dream steady.

Since he graduated from the prestigious Bullis High School in Potomac — where his parents sent him because they had such high hopes — people have been telling him he must be crazy to ride so fast, to not settle down, to not get a real job. Now, things might be falling into place. Kelley swears he can see fame. It’s up ahead, closer than it ever has been, and he’s riding as fast as he can to get there, trying not to crash. Again.

The stunts are a means to an end for him.

And for a couple of his guys, the stunts might just be the end itself.

On the Road Again

It’s a late August afternoon and for miles along Route 236 in pastoral St. Mary’s County, Streetbike Tommy — Tommy Passemante, 21, who lives in Annapolis — sits in the back of a Chevrolet pickup shooting video while the Crew runs through stunts. A photographer for Loaded, a popular British men’s magazine, has been shooting them all day, too.

With the pickup cruising in front of them at 33 mph, the motorcyclists stunt on the open road, taking up both lanes. Traffic backs up behind them, some of the drivers looking angry, some awed. The guys stop stunting when cars pass them from the opposite direction. An Amish man driving his buggy passes and steadies his horse, which is frightened by the half-dozen riders.

It’s a traffic violation to do a wheelie on a public road, and the guys are always on the lookout for the police. Most have had their licenses taken multiple times. Last year, stunt cyclist Shaun P. Matlock crashed into a parked tow truck in Frederick and died while an extreme-games sports promoter from Baltimore filmed him. But Brian Cedar, commander for the Maryland State Police in St. Mary’s County, called that fatality an isolated incident. The biggest problem is spectators trying to do stunts they see at events, he says. A few years ago they rounded up about a dozen riders who were popping wheelies and speeding.

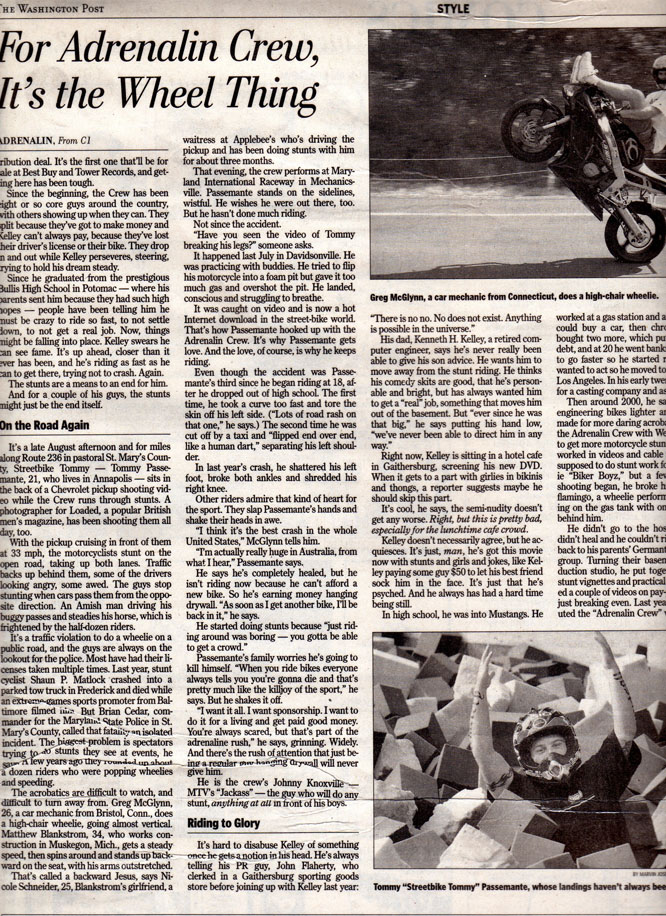

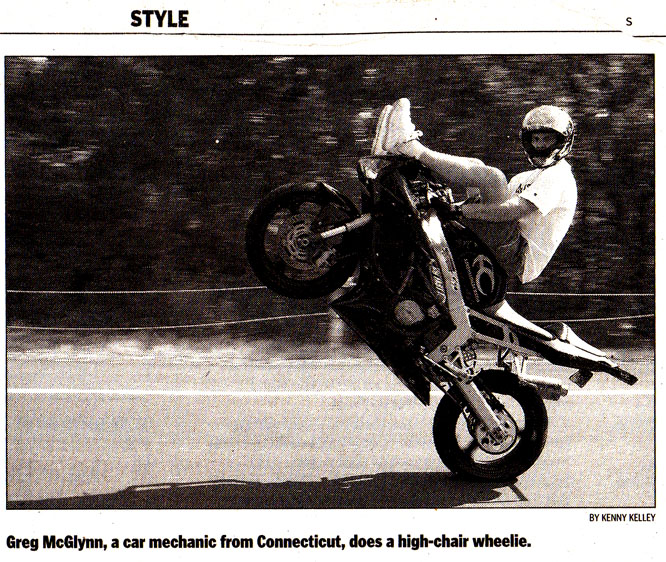

The acrobatics are difficult to watch, and difficult to turn away from. Greg McGlynn, 26, a car mechanic from Bristol, Conn., does a high-chair wheelie, going almost vertical. Matthew Blankstrom, 34, who works construction in Muskegon, Mich., gets a steady speed, then spins around and stands up backward on the seat, with his arms outstretched.

That’s called a backward Jesus, says Nicole Schneider, 25, Blankstrom’s girlfriend, a waitress at Applebee’s who’s driving the pickup and has been doing stunts with him for about three months.

That evening, the crew performs at Maryland International Raceway in Mechanicsville. Passemante stands on the sidelines, wistful. He wishes he were out there, too. But he hasn’t done much riding.

Not since the accident.

“Have you seen the video of Tommy breaking his legs?” someone asks.

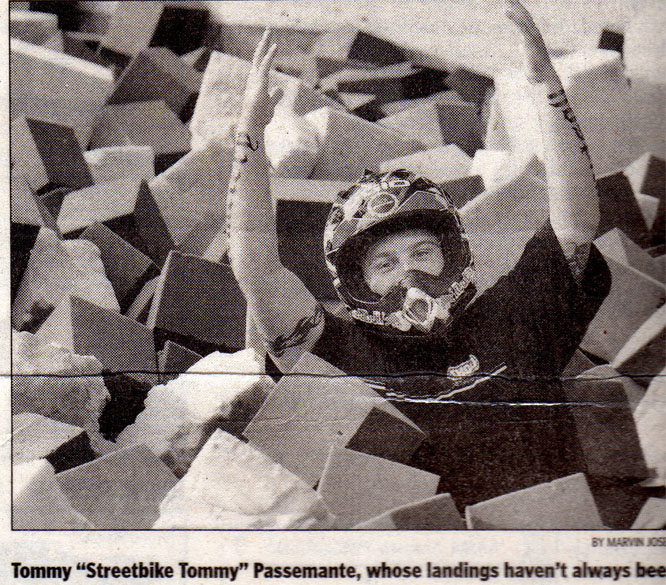

It happened last July in Davidsonville. He was practicing with buddies. He tried to flip his motorcycle into a foam pit but gave it too much gas and overshot the pit. He landed, conscious and struggling to breathe.

It was caught on video and is now a hot Internet download in the street-bike world. That’s how Passemante hooked up with the Adrenalin Crew. It’s why Passemante gets love. And the love, of course, is why he keeps riding.

Even though the accident was Passemante’s third since he began riding at 18, after he dropped out of high school. The first time, he took a curve too fast and tore the skin off his left side. (“Lots of road rash on that one,” he says.) The second time he was cut off by a taxi and “flipped end over end, like a human dart,” separating his left shoulder.

In last year’s crash, he shattered his left foot, broke both ankles and shredded his right knee.

Other riders admire that kind of heart for the sport. They slap Passemante’s hands and shake their heads in awe.

“I think it’s the best crash in the whole United States,” McGlynn tells him.

“I’m actually really huge in Australia, from what I hear,” Passemante says.

He says he’s completely healed, but he isn’t riding now because he can’t afford a new bike. So he’s earning money hanging drywall. “As soon as I get another bike, I’ll be back in it,” he says.

He started doing stunts because “just riding around was boring — you gotta be able to get a crowd.”

Passemante’s family worries he’s going to kill himself. “When you ride bikes everyone always tells you you’re gonna die and that’s pretty much like the killjoy of the sport,” he says. But he shakes it off.

“I want it all. I want sponsorship. I want to do it for a living and get paid good money. You’re always scared, but that’s part of the adrenaline rush,” he says, grinning. Widely. And there’s the rush of attention that just being a regular guy hanging drywall will never give him.

He is the crew’s Johnny Knoxville — MTV’s “Jackass” — the guy who will do any stunt, anything at all in front of his boys.

Riding to Glory

It’s hard to disabuse Kelley of something once he gets a notion in his head. He’s always telling his PR guy, John Flaherty, who clerked in a Gaithersburg sporting goods store before joining up with Kelley last year: “There is no no. No does not exist. Anything is possible in the universe.”

His dad, Kenneth H. Kelley, a retired computer engineer, says he’s never really been able to give his son advice. He wants him to move away from the stunt riding. He thinks his comedy skits are good, that he’s personable and bright, but has always wanted him to get a “real” job, something that moves him out of the basement. But “ever since he was that big,” he says putting his hand low, “we’ve never been able to direct him in any way.”

Right now, Kelley is sitting in a hotel cafe in Gaithersburg, screening his new DVD. When it gets to a part with girlies in bikinis and thongs, a reporter suggests maybe he should skip this part.

It’s cool, he says, the semi-nudity doesn’t get any worse. Right, but this is pretty bad, especially for the lunchtime cafe crowd .

Kelley doesn’t necessarily agree, but he acquiesces. It’s just, man , he’s got this movie now with stunts and girls and jokes, like Kelley paying some guy $50 to let his best friend sock him in the face. It’s just that he’s psyched. And he always has had a hard time being still.

In high school, he was into Mustangs. He worked at a gas station and at Best Buy so he could buy a car, then chrome it out. He bought two more, which put him heavily in debt, and at 20 he went bankrupt. He wanted to go faster so he started riding bikes. He wanted to act so he moved to New York, then Los Angeles. In his early twenties, he worked for a casting company and as an extra.

Then around 2000, he says, they started engineering bikes lighter and faster, which made for more daring acrobatics. He started the Adrenalin Crew with West Coast friends to get more motorcycle stunts in movies. He worked in videos and cable movies and was supposed to do stunt work for the 2003 movie “Biker Boyz,” but a few weeks before shooting began, he broke his wrist doing a flamingo, a wheelie performed while standing on the gas tank with one foot extended behind him.

He didn’t go to the hospital. His wrist didn’t heal and he couldn’t ride, so he moved back to his parents’ Germantown home to regroup. Turning their basement into a production studio, he put together motorcycle stunt vignettes and practical jokes, then landed a couple of videos on pay-per-view, mostly just breaking even. Last year, he self-distributed the “Adrenalin Crew” video, which got distribution deals overseas.

But for years he has been calling and e-mailing and “stalking” Hollywood guys who could take him to another level. “He’s the most confident producer in the world,” says Eric Boyd, CEO of Los Angeles-based Destroy Entertainment, which is distributing “100% Illegal” through Warner Music Group. “Everything he touches is the best, he said. He called us for 12 months, twice a week.”

Adrenalin Crew members provide much of the raw material for the DVD. There’s Kelley being handcuffed in Daytona Beach for riding on a suspended license, and again in Los Angeles for racing. He has been cited 27 times for traffic violations since 1995 in Maryland alone.

Some of the footage is sent in. There’s Streetbike Tommy’s crash. “I’m tearing it up for your amusement,” he tells the camera. At one point he’s seen throwing up after drinking too much. Can’t really say what he does next, but really this guy will do anything in front of his boys.

Toward the end, there are scenes of just the riders, graceful, poetic even, in their acrobatics. And dangerous.

Kelley didn’t know the Matlock guy who got killed, but felt bad about what happened. He doesn’t solicit or pay for footage sent in. He uses only experienced riders. “We calculate, everything’s planned out, my guys are professionals,” he says. “Still, I can’t justify what I do to a mother.”

He just doesn’t know how else to get to that place he’s fantasized about.

He wishes there were a track where the stunts could be performed more safely: “I don’t want people to watch this and be horrified, I want them to watch it and be entertained.” He wants that feeling like he got last week when he pulled up to a light doing an endo and a bus full of high-schoolers cheered.

Born to Perform

At the Criswell’s open house, Kelley is filming Van — 23-year-old William Vance Cummings from Alexandria. Cummings is not wearing a helmet. He’s not hamming. He’s not smiling. His blue eyes are steely. He pulls into a high wheelie, stands up, then looks straight at the camera. He’s the motorcycle purist of the Adrenalin Crew.

At the Criswell’s open house, Kelley is filming Van — 23-year-old William Vance Cummings from Alexandria. Cummings is not wearing a helmet. He’s not hamming. He’s not smiling. His blue eyes are steely. He pulls into a high wheelie, stands up, then looks straight at the camera. He’s the motorcycle purist of the Adrenalin Crew.

“I got a bike because I thought they looked tight, then I started wheeling it,” says Cummings, a UPS supervisor in Gaithersburg. “I used to get off of work and ride until 5 in the morning. I’d go out and ride and try anything.”

Even if he weren’t riding at Criswell’s today, he’d be riding. “That’s a normal day for me right there, riding. That’s all I do. That’s all I think about.”

Kelley, taking video, sees that in him. “Look at him, he was born to ride,” he says. And Kelley was born to steer that drive. “There’s all these characters out there riding and they’re doing little crappy videos that nobody sees. I’ve given him a chance to mainstream.”

Kelley swears he can see fame.

A spectator walks by and Kelley is momentarily weirded out. That can happen when something you’ve obsessed about looks like it’s right there, man, right around the corner: The guy was wearing an Adrenalin Crew T-shirt. Now, they’re wearing his T-shirts !

It’s real cool, you know, but of course, it’s not nearly enough